Texto original en inglés y traducción al castellano de Lucía Cornejo

I have often wondered what obscure forces impel Mexicans to relish the unbearably acrid hot peppers used as condiment in their food. A dual psychological inheritance comes to mind. First, the dark impetus of sacrifices to the bloody Aztec monolith; second, the no less ominous attitude of Spanish mystics, who saw the body as a contemptible burden that impedes the spirit to soar and must be subjugated with austerities, penance, privation, and mortification. Only the conjunction of these two body-loathing propensities may explain the subversion of the pleasurable experience of eating, and its transformation into a painful sacrifice. This, of course, applies only to the uninitiated. Those of us who were born and raised in the ancestral land of the obsidian-knife sacrificers and the gaunt, sackcloth-and-ashes Castilian anchorites, are supposed to undergo a period of training that renders the oral mucosa insensitive to the fiercest attacks of capsaicin-rich seeds. This has been part of the culture for centuries.

To the chagrin of my father, I deviated from this venerable tradition, for I simply could not stand the training. As a child I was given a small plate filled with hot sauce by my authoritarian father. The gesture and the adjoined supercilious gaze were a mute but unmistakable command to spread a good portion of the devilish concoction on my food. My timidity, and the meagerness of my serving, gave him umbrage. But my tearful reaction when, having tasted a thin film of the sauce, I felt as if I had a live coal inside my mouth, was too much for him. He vented his annoyance with an irritated “What’s the matter with him? Is he not a Mexican?”

The utterance was indirect: although meant to indict me, it was at the same time an appeal to a higher authority, namely that of my mother. Hers was the last word in everything that concerned my upbringing. To her unyielding protection I owe, among countless other benefactions, the preservation of an intact oral mucosa. For those caustic seasonings, apt to melt cast iron, no doubt would have bored holes through a boyish tongue.

On the other hand, gastronomical harshness was only part of my father’s apprehension of the world and his grim philosophy of life. It was his lot to have lived through a period of collective savagery euphemistically called “the Revolution.” He took part in combat, on the losing side. That was a time when rashness and audacity profited a man more than industry and moderation; when fortunes were made and unmade in a moment, according to the shifting winds of political passions; when the legitimate powers were toppled by bold men who came professing equality for all, only to usurp the very same authority which they slandered. Timeless values were abrogated, only the present counted, and the only certainty was the imminence of death. From all this my father distilled a rude male version of stoicism. Be strong. Never flinch. Effeminacy equals weakness. And his inflexible motto: “Men don’t cry.”

When the troubles were over, he found himself out of phase with the world. Lacking the skills to prosper in the new era, he expected his past sufferings to earn him fresh rights. Alas, he was confronted by men whom he inwardly despised, but who mocked his pride and derided his intrepidity while asserting their authority over him. Vauvenargues proclaimed that “peace makes the people happy, but the men weak.”1 This is how he felt. Embittered upon realizing his war prowess was ignored by the new government, he should have heeded the great bard’s warning:

“The painful warrior famoused for fight

After a thousand victories once foiled

Is from the book of honor razed quite,

And all the rest forgot for which he toiled.”2

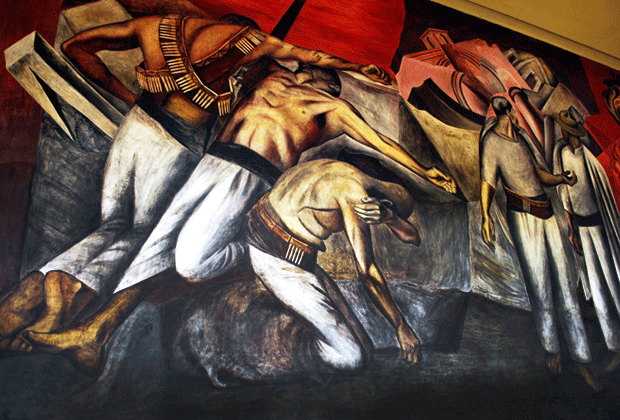

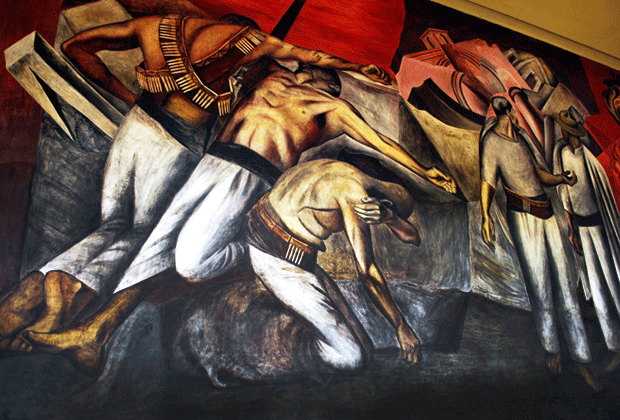

Instead, he tried to smother his rancor and disappointment in alcohol. What bullets could not do, the spirituous fumes easily accomplished: his internal organs were irreparably destroyed. I once saw him unconscious, emaciated, jaundiced, and unkempt, looking nothing so much like the wounded revolutionist in Orozco’s mural “The Trench”. Lying exanimate, consumed, arms outstretched, the man’s image in the mural evokes crucifixion more strongly than gunshot trauma.

When he saw his death approach, he asked, in plaintive tones, to be taken to his mother’s home, deep in the province. Uncharitable critics said that he faltered: where had all his bluster gone? Such is the invidiousness and malice of the world toward those who at the last minute recant the opinions or principles they formerly professed. As if finding oneself in an inexpressible predicament—the most vulnerable situation possible for any human being—was not sufficient cause for seeing things differently.

I could never absorb my father’s stoic “machismo,” today obsolete and perhaps risible. But the raw spectacle of his life made me reflect that a way to lessen suffering is to distance ourselves from life’s fray and tumult. Oriental philosophies attempt to teach us this. If the pain is too great here and now, learn to regard it “as if” you were thousands of miles above it, in a timeless vantage point. St. Paul’s thought must have followed this drift when he advised those who have wives “to live as if they had none.”3 Not that he wanted them to put away their spouses, but to live as if nothing was their own. For nothing in this world is really ours, in real or permanent possession.

To live “as if” we were not really living... easier said than done! But if this “holy indifference of the world” is unattainable, the outward expression of sentiments can be faked. This I discovered while attending my father’s funeral wake when I was ten years old.

Women wrapped in black rebozos (shawls) sat around the open coffin, which rested on a high support. My small stature did not allow me to look inside. As was customary, there was a table with coffee and victuals to sustain the women in their incessant recitation of rosaries and litanies. “The duty of women is to cry for the dead. That of men is to remember them.”4 This insensitive saying of Tacitus accorded well with the scene. Someone lifted me by the waist, that I should “see my father for the last time.” The sight was neither necessary nor consoling or edifying: a broken man, exhausted and devastated by the combined assaults of utter despair and liver cirrhosis. I would rather not have seen him thus.

All eyes were fixed on me. I was confused, embarrassed, and discomposed. An intimate disheartenment, a strange mixture of repulsion and enervation invaded me. At the same time, all the women kept looking at me. The officious man who had lifted me without asking for my permission deposed me again on the floor. Then I experienced something like a vacuum, a never-to-be-filled hole in my existence. A sort of inchoate sob was taking shape deep inside me.

Not quite knowing what I was doing, I approached the table with the food on it, took the wooden spoon dipped in hot sauce, and immersed it fully into my mouth.

The face flushing, the gestural contortions, and the abundant lacrimation that followed were attributed to my childish imprudence. “The poor darling! He did not know that was the hot sauce!” commented the women who came to relieve my distress with sugary beverages and towels. Meanwhile, in my heart of hearts, I felt proud. I had fooled everyone into thinking that physiology and capsaicin, not forlornness and a son’s sorrow, were the true cause of my tears. Had my father seen me, he certainly would have approved. Men don’t cry.

1 Luc de Clapiers, Marquis de Vauvenargues: Réflexions sur divers sujets. In: Œuvres Complètes. Vol. 1. Paris, Brière, 1827

2 William Shakespeare: Sonnet XXV. May be consulted online: http://www.shakespeares-sonnets.com/sonnet/25

3 St. Paul: 1 Corinthians 7: 29.

4 Quoted by Henry de Monthérland in: Mors et Vita. In Essais de Monthérland. Paris. Gallimard. Collection Pléiade. 1963, p. 510.

Agradecemos a la revista electrónica Hektoen International su autorización para incluir este texto en Biblioteca de México: https://hekint.org/2018/08/17/fire-eaters/

Con frecuencia me he preguntado qué fuerzas oscuras llevan a los mexicanos a deleitarse con los chiles insoportablemente acres con los que condimentan su comida. Una doble herencia psicológica me viene a la mente: primero, el oscuro ímpetu por ofrecer sacrificios al sangriento monolito azteca; en segundo lugar, la no menos ominosa actitud de los místicos españoles que veían el cuerpo como una carga despreciable que impedía la elevación del espíritu y que debe subyugarse con austeridades, penitencia, privaciones y mortificación. Sólo la conjunción de estas dos inclinaciones que desprecian el cuerpo podría explicar la subversión del comer como experiencia placentera y su transformación en un sacrificio doloroso. Esto, claro, aplica sólo a los no iniciados. Aquellos de nosotros que nacimos y crecimos en la tierra ancestral de los sacrificadores de cuchillo de obsidiana y los anacoretas demacrados en silicio y en ceniza, debemos atravesar un período de entrenamiento que hace a la mucosa oral insensible a los ataques más fieros de las semillas ricas en caseína. Esto forma parte de la cultura desde hace siglos.

Para el disgusto de mi padre, yo me desvié de esta venerable tradición porque simplemente no podía soportar el entrenamiento. Cuando era niño me dieron un plato pequeño que mi autoritario padre había llenado de salsa picante. Su expresión, además de su mirada desdeñosa, fueron una silenciosa pero inconfundible orden de untar una generosa porción del diabólico menjurje en mi comida. Él resintió mi timidez y la mínima cantidad de mi porción. Pero mis lágrimas, al sentir como si tuviera brasas al rojo vivo en la boca después de probar unas cuantas gotas de salsa, fueron demasiado para él; desahogó su enojo con un irritado “¿Qué le pasa? ¿a poco no es mexicano?”.

Su declaración era indirecta: aunque tenía la intención de culparme, al mismo tiempo apelaba a una autoridad mayor: es decir, a la de mi madre. La suya era la última palabra en todo lo relacionado con mi crianza. A su protección sin tregua le debo, entre otros favores innumerables, la preservación de una mucosa oral intacta. Ya que aquellos sazonadores cáusticos, aptos para derretir el hierro, sin duda habrían dejado huella en la lengua de un niño.

Por otro lado, la dureza gastronómica era sólo una parte de la visión del mundo de mi padre y su sombría filosofía de vida. Su conflicto fue el haber vivido durante un período de brutalidad colectiva llamado eufemísticamente La revolución. Él participó en el enfrentamiento, del lado perdedor. Se trataba de un tiempo en el que la impulsividad y la audacia, más que la diligencia y la moderación, beneficiaban a los hombres; cuando, de acuerdo con los constantes cambios de viento de las pasiones políticas, la suerte se decidía y se derrumbaba en un instante; cuando los poderes legítimos eran demolidos por hombres audaces que llegaban pregonando igualdad para todos sólo para usurpar la misma autoridad que condenaban. Se abolían valores de antaño, sólo el presente contaba y la única certeza era la inminencia de la muerte. De todo esto mi padre adquirió una especie de estoicismo rudo y masculino: sé fuerte. Nunca te doblegues. Lo afeminado es igual a debilidad. Y su lema inquebrantable: los hombres no lloran.

Cuando todo acabó, mi padre se encontró a sí mismo desconectado del mundo. Sin las habilidades necesarias para prosperar en la nueva era, él esperaba que sus sufrimientos pasados le concedieran nuevos derechos. Es decir, fue confrontado por hombres a quienes internamente despreciaba, pero que se burlaban de su orgullo y su intrepidez al mismo tiempo que afianzaban su autoridad sobre él. Vauvenargues afirmaba que “la paz hace feliz a la gente, pero débiles a los hombres.”1 Así se sentía. Amargado al darse cuenta de que el nuevo gobierno ignoraba su pericia para el combate, debió escuchar la advertencia del gran bardo: “El sufrido guerrero, famoso en el combate, / tras mil victorias, ve, si una vez le derrotan, / cómo pronto es borrado del libro del honor / y se olvidan las causas por las cuales luchó.”2

En cambio, mi padre trató de ahogar su rencor y su decepción en alcohol. Los vapores espirituales lograron fácilmente lo que las balas no: sus órganos internos estaban destruidos de forma irreparable. Una vez lo vi inconsciente, demacrado, cenizo y deshecho; no muy distinto del revolucionario herido en el mural de Orozco “La trinchera”. Desfallecido, recostado con los brazos estirados, la imagen del hombre del mural evoca más bien la crucifixión que las heridas de bala.

Cuando sintió que su muerte estaba cerca, pidió, con tono lastimero, que se le trasladara a la casa de su madre en provincia. Los críticos sin caridad decían que flaqueaba: ¿dónde había quedado todo su vigor? Tal es la ingratitud y la malicia del mundo hacia aquellos que en el último minuto se desdicen de las opiniones o principios que profesaron toda la vida. Como si el encontrarse uno mismo en un predicamento inexpresable –la situación más vulnerable posible para cualquier ser humano— no fuera causa suficiente para ver las cosas de manera distinta.

Nunca pude adquirir el machismo estoico de mi padre, hoy obsoleto y quizá risible. Pero el crudo espectáculo de su vida me hizo reflexionar sobre que una manera de aminorar el sufrimiento es distanciarnos del desgaste y el caos de la vida. Las filosofías orientales intentan enseñarnos esto. Si aquí y ahora el dolor es demasiado, aprende a verlo como si estuvieras a miles de kilómetros por encima de él, o contemplándolo desde otro lugar. El pensamiento de San Pablo debe haber ido en esta línea cuando aconsejó a aquellos que tienen esposas el “vivir como si no tuvieran ninguna”3 No se refería a que se deshicieran de ellas, sino a que vivieran como si nada les perteneciera, ya que nada en este mundo es realmente nuestro en posesión real o permanente. Vivir como si no se viviera realmente... ¡más fácil decirlo que hacerlo! Pero si esta sagrada indiferencia hacia el mundo es inalcanzable, la exteriorización de los sentimientos puede fingirse. Esto lo descubrí al asistir al funeral de mi padre cuando tenía diez años.

Había mujeres envueltas en rebozos negros que estaban sentadas alrededor del ataúd abierto y elevado encima de un soporte. Mi pequeña estatura no me permitía mirar hacia dentro. Como era la costumbre, había una mesa con café y provisiones para alimentar a las mujeres que recitaban incesantes rosarios y letanías. “El deber de las mujeres es llorar a los muertos. El de los hombres es recordarlos”.4 Este dicho insensible de Tácito iba bien con la escena. Alguien me alzó por la cintura, porque yo debía ver a mi padre por última vez. La visión no era necesaria, ni fue consoladora o edificante: sólo un hombre roto, exhausto y devastado por combinados arranques de desesperanza y cirrosis hepática. Habría preferido no verlo.

Todos me miraban. Yo estaba confundido, avergonzado y perturbado. Una desesperanza íntima, una extraña mezcla de repulsión y enervación me invadieron. Todas las mujeres seguían mirándome al mismo tiempo. El entrometido que me había alzado sin preguntarme me puso de nuevo en el suelo. Luego sentí como un vacío, un hueco en mi existencia que nunca podría llenarse. Una especie de sollozo incipiente empezaba a formarse dentro de mí.

Sin saber bien lo que hacía, me acerqué a la mesa con comida, tomé la cuchara de madera metida en salsa picante y la metí por completo en mi boca.

La cara sonrojada, las contorsiones faciales y el lagrimeo abundante que siguieron se atribuían a mi imprudencia infantil. “¡Pobrecito! ¡No sabía que era la salsa picante!”, comentó la mujer que vino a sacarme de mi dolor con toallas y bebidas azucaradas. Mientras tanto, en mi fuero interno, me sentía orgulloso. Había engañado a todos para que pensaran que la fisiología y la caseína, no la tristeza y el dolor de un hijo, eran la verdadera causa de mis lágrimas. Si mi padre me hubiera visto, seguramente se hubiera sentido orgulloso. Los hombres no lloran.

1 Luc de Clapiers, Marquis de Vauvenargues: Réflexions sur divers sujets. En: Œuvres Complètes. Vol. 1. Paris, Brière, 1827

2 William Shakespeare: Soneto XXV. Puede ser consultado en su versión en inglés en: http://www.shakespeares-sonnets.com/sonnet/25 Consultado en su versión en español en: https://bit.ly/3hcdVRK

3 San Pablo: 1 Corintios 7: 29.

4 Citado por Henry de Monthérland en: Mors et Vita. En Essais de Monthérland. París. Gallimard. Collección Pléiade. 1963, p.510.

Agradecemos a la revista electrónica Hektoen International su autorización para incluir este texto en Biblioteca de México: https://hekint.org/2018/08/17/fire-eaters/

Francisco González-Crussí nació y creció en México. Hasta su retiro en 2001, fue jefe de laboratorios del Children’s Memorial Hospital of Chicago (ahora llamado Anne & Robert Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago). Ha escrito veinte libros de ensayos en español e inglés. Su reciente obra Carrying the Heart (Kaplan, 2009), que reúne elementos de la medicina y las humanidades, obtuvo el Premio Letterario Merck (Roma, 2014).

Lucía Cornejo, traductora de este ensayo, es maestra en traducción por El Colegio de México. Fue becaria de la Fundación para las Letras Mexicanas (2018-2020). Algunos de sus poemas y traducciones aparecen en distintos medios y revistas digitales e impresas como Novísimas. Reunión de poetas mexicanas (1989-1999) (Los libros del perro, 2020), Punto de Partida, Letras Libres y Este País.